Shoshi Bar-Eli and Keren Dvir

The preliminary model described is based on a two-year ongoing experimental pilot with a working community of professional development experts. The challenge is to reframe professional development as a complex problem, perceiving it within the context of trans-disciplinarity. Innovative methodologies from the design field were adapted in an innovative manner. This article describes the model, focusing on the first tool: "visual path as a representation of organizational culture".

Keywords | professional development, trans-disciplinary, visual tools, DESIGN, ORGANIZATIONAL culture

1. Introduction

Dramatic changes in society, technology, economics, environment, and politics are occurring at an accelerated pace. The complexity and rapid changes of the future environment require a dramatic transformation in the organizational culture of professional development. “Professional development has recently come to be viewed as a long-term process, covering different types of opportunities and experiences" (Marcelo, 2009). This idea was reinforced by the 2018 World Economic Forum’s ‘Future of Jobs’ Report.

"By 2022, no less than 54% of all employees will require significant re- and upskilling. Companies themselves will need to take the lead in creating capacity within their organizations to support their transition towards the workforce of the future" (WEF, Future of jobs report, p.x).

“Central to the success of any workforce augmentation strategy is the buy-in of a motivated and agile workforce, equipped with futureproof skills to take advantage of new opportunities through continuous retraining and upskilling" (WEF, Future of jobs report, p. 12). The responsibility for adapting to these changes is on the worker. As stated, "there is an unquestionable need to take personal responsibility for one’s own lifelong learning and career development. It is equally clear that many individuals will need to be supported through periods of job transition and phases of retraining and upskilling by governments and employers" (ibid, p.23). Shaperling (2018), as part of a report on the effectiveness of professional development in the educational system, indicated that most programs do not produce the expected results, and do not sufficiently contribute to student achievement. The current didactive models are not effective. There is a need for innovative collaborative models, in which teachers become active in their professional development decisions.The question of professional development should be treated as a complex design problem. This challenge is being undertaken through a two-year pilot project with a working community group of experts in teacher’s professional development.

Our project is led, initiated and analyzed by an architect-researcher focused on design education problem solving and design behavior profiles, and a specialist in assessment and evaluation. Two other partners are the Ministry of Education’s Division for Research-Development-Experiments and Initiatives, and Professional Development. The goal is to improve the existing model of professional development, while catering to teacher diversity, quickly implementing the model throughout the 60 national centers, known as ‘Psagot.’

The preliminary model described in this article is based on re-framing professional development as a complex problem, and perceiving it within the context of trans-disciplinarity. Within the process, innovative methodologies from the Design field were adapted. Methodologies of experimentation were implemented using visual representation, interchanging various types of reflections and analysis. This collaborative research presents the development of a unique case-study, based on knowledge and experience in the researchers' respective fields.In this article the professional development model will be generally described, and the focus of discussion will be around one of the model tools: "visual path as a representation of organizational culture".

2. Theoretical background

2.1 Re-framing Professional development as a complex problem

When treating professional development as a complex problem, it should be viewed as “ill-defined” (Eastman, 2001; Simon, 1973, 1995), and “wicked and open ended” (Rittel & Webber, 1984). Its solutions must be both new and adapted to the characteristics of the situation or context, including future users and usages (Bonnardel, 2012). This twofold requirement directly corresponds to definitions of creativity, which can be viewed as the ability to produce work that is both novel and appropriate (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999).

The first step in the problem-solving process is to determine whether a problem actually exists. The problem solver must determine what the nature of the problem is. As stated by Dorst, the act of framing is "to create a new approach to problem situations" (Dorst, 2015,2). Therefore, identifying an appropriate problem space among competing options is perhaps the most important part of ill-structured problem solving. According to Cross and Cross the act of framing the problem is central to the ability to innovate (Cross and Cross, 1998). The first phase of the pilot was to follow the above principles, treating professional development as a complex problem, defining its components, conflicts and boundaries.

2.2 Trans-disciplinary Professional development

Trans-disciplinarity, as opposed to multi-disciplinarity and inter-disciplinarity, concerns that which is simultaneously between disciplines, across different disciplines, beyond all disciplines. Its goal is to understand the present world, of which one imperative is the unity of knowledge (Nicolescu, 2005). According to Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn, this requires that we "grasp the complexity of problems; take into account the diversity of life-world and scientific perceptions of problems; link abstract and case-specific knowledge, and develop knowledge and practices that promote what is perceived to be the common good” (Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn, 2007, 20).

The practical implication of Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn’s research is a new perception of professional development as an innovative kind of thinking and doing, including four main emphases: Developing a new amalgamation of methodologies, enabling a fresh approach to the existing situation, including the following principles: Large enough to see clearly;

- Use of visual tools.

- Active experience.

- Flexibility/agility: both characterize the ability to work under conditions of

- Relevance: despite the trans-disciplinary approach, there is a need to take into account specific targeted population.

- Constant reference to diversity of knowledge, context and people.

- Constant interchanging between Individual and group.

- Constant de-construction/re-construction of knowledge, context and behaviour.

Extracting personalized responses from an agile general solution:

- This principle strengthens the idea of personalization; developing general solutions that could be related, in a simple process of identification, to various peoples' profiles.

Developing a working community:

- Working Communities function as a group of self-developing experts. These active communities, recommended by Shaperling (Shaperling, 2018) are a highly significant resource, allowing for the complex examination of needs, practices, and solutions development. Working Communities enable an active and simultaneous process of thinking, implementing and reflecting. They are vital to sharing the process, and monitoring development through various types of analysis so that products can be effectively applied in the field.

Appropriation of the model and its tool by the participants:

- Along with the results of previous research studies, current prescriptive/descriptive models are not effective. We propose a model that serves as a platform for the ongoing creation and development of innovative solutions for a diverse set of user profiles.

2.3 Reflection and Visual Representation

The notion of reflection is intertwined with the notion of visualization and visual representation. The major challenge is finding the right visual representation for the specific type of content, and integrating it with specific exercises, using various types of reflections.

Arcavi proposes the definition of visualization as "the ability, process and product of creation, interpretation, use of and reflection upon pictures, images, diagrams, in our minds, on paper or with technological tools, with the purpose of depicting and communicating information, thinking about and developing previously unknown ideas and advancing understandings" (Arcavi, 2003, 26).

Schön was one of the seminal researchers to recognize the interconnection between visualization, representation and reflection. Schön's main claim was that design is a "reflective conversation with the situation"; meaning that, during the design process, the designer enters into a "frame experiment," a "dialogue" with the materials of the situation (Schön's, 1983;1987). Schön discusses the activity of design, and speaks about different kinds of reflections: reflection in action, reflection on action and reflection on practice. He says: "Reflection in action is closely related to the experience of surprise. Sometimes, we think about what we are doing in the midst of performing an act" (Bennett, 1996, p. 172). This reflective act is due to the constant iteration between sketching combined with talking.

"In some situation the designer exhibits a reflection on action, pausing to think back over what she has done in a project, exploring the understanding that she has brought to the handling of the task". (Bennett, 1996, p.172). In a third kind of reflection, reflection on practice, the designer may surface and criticize tacit understandings that have grown around repetitive experiences of designing." (Bennett, 1996, p.172) This act of alternating between visual representation and various types of reflection is highly important for the ability to be creative and generate creative concepts. We believe it must be adapted to other non-design environments. The type of visual representation should be carefully chosen, intertwined with the content-at-hand, and be suited to the participants' knowledge and abilities.

3. Pilot description

The pilot project is a collaboration between the Ministry of Education’s Division for Research-Development-Experiments and Initiatives, and Professional Development. The Division is responsible for guidance, development, validation and evaluation in accordance with strategic and systemic policy needs. It was decided to focus on “Psagot” – teachers' professional development centers, which are responsible for providing up-to-date responses to the needs of teaching staff throughout their career. Today, there are around 60 Psagot centers around the country, serving around 100,000 teachers each year.

3.1 The participants

The working community, comprised of Psagot managers, vice managers and key workers, was recruited through a call for participation, followed by an interview with the researchers. Twenty participants from seven centers were chosen for the pilot project. The working process with the group included physical meetings, on-line discussions, and researcher visits to various centers. Additionally, the model was tried out in a 20-hour workshop of Psagot mangers, as part of their professional development program (not including the 7 centers of the working community).

3.2 Pilot Layout

The pilot includes various successive phases. Each phase employs different tools. These principles are incorporated throughout the entire process, including the following:

- Visual Path of organizational culture.Defining the gap between the existing and what is desired by starting with the personal, immediately moving to the group.

- Amalgamating Assets: creative process of finding resources through use of sequential contextual photograph

- Extracting core challenges, and generating a comparative analysis process.

- User Experience: understanding individual differences and unique needs. Storytelling, analysis of general needs, interviews.

- Strategic Mapping, choices of project development.

- Creative dialogue: Designing a simulation addressing various parameters of the chosen development project. Combining of self/resources/people by experiencing.

Here, we focus only on the first phase:

3.3 Visual Path

The actual tool is a revision and combination of several existing tools: Card Sorting, and Brainstorm Graphic Organizer (Hanington and Martin, 2012, 5, 22). Card sorting: participatory design technique exploring the way items are grouped into categories and relate to one another.

Brainstorming: used to spur creativity with the intention of generating concepts and ideas regarding a specific challenge. Diagrams of all sorts are added to help visualize the network of ideas. In many cases, diagrams are given in advance. The diagram should be intertwined with the development of ideas to strengthen the iteration of visual representation and reflection. This is one of the main principles of the current project and research.

The tool’s three assignments.

Assignment 1- two questions, done individually

- As a Professional Development Expert, what do you think you can contribute?

- As a Professional Development Expert, what would you like to receive? Write freely and select 2 statements.

Assignment 2- (done in groups) All participant statements should be organized in a path that describes linkages and connections. Explain the decision-making process and the criteria for creating the path. Throughout the assignment, the researchers observe the various actions being taken.

Assignment 3- reflection on "Visual path of organizational culture". The purpose is to creatively examine the tool. It can be done by applying the tool to other specific populations such as school principals, teachers, administrators, and more.

The analysis was done through three types of reflections:

- Reflection in Action – Immediate processing done by participants and facilitator.

- Reflection on Action – Analysis based on results. Discussing implication of the tool in various levels.

- Reflection on Practice – Analysis of the tool’s implication on professional development strategy, discussion with Ministry of Education division responsible for teacher’s professional development.

3.4 Rationale behind the tool

The first phase established the state of mind and inspiration for the entire project. The challenge was to interconnect all the main principles of trans-disciplinarity, to reframe professional development as a complex problem. We wanted to design a warm-up and experimental assignment using visual tools that enable groups to clearly and transparently "see" their current perceptions and values. This concept is the first step in understanding problems of professional development, an essential need for group development.

To define the gap between the existing situation and what is desired, the tool was built on continuous iterations between individual/group, abstract/concrete, and visual representation/reflections. All the above are central characteristics of design processes adopted to the current project. Other main principles of the tool are:

- Agility and uncertainty – the purpose of using the tool is not visible to the participants.

- Easily implemented and understood as a visual assignment. Allow people to act freely, creatively, for later use and complex analysis.

The complexity of the tool lies in its stages; from personal story and dilemma (the individual), to a group creation, to find clear principles or concepts, allowing for development of a complex relation of ideas.

4. Results

The pilot was conducted among two similar populations of working group and workshop populations. In both cases, participants were asked to fill out cards, answering the questions: As a Professional Development Expert, "what do you think you can contribute?" and "what would you like to receive?"

4.1 Visual path of the Working Community from the 7 Psagot Centers.

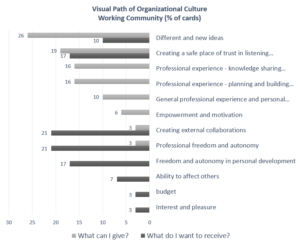

The participants' answers on the cards were analyzed. Figure 1 describes the distribution of answers. The chart shows that among the working group participants there is a clear distinction between what they can contribute, such as new ideas, creating a safe place, professional experience, empowerment and motivation, and the things they want to receive: collaborative professional and personal freedom, autonomy, effect on others, budge

Figure 1 : Analysis of participant's responses.

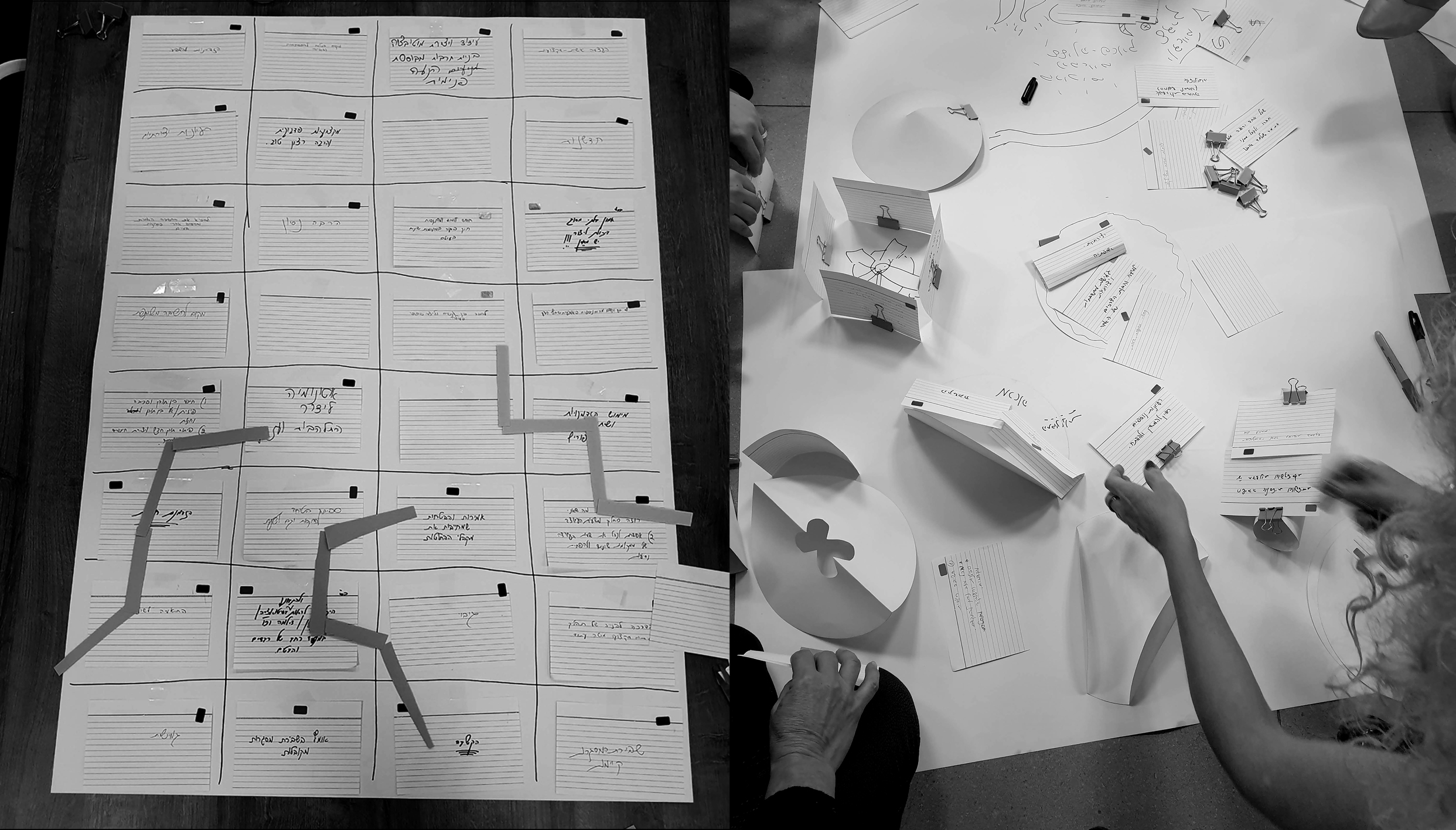

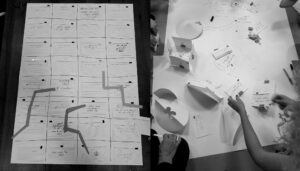

The participants were divided into two groups in different work spaces to build the path describing the professional development process, and began discussions about the shape of the path. Quite quickly, participants in both groups came to define their path as a game track. One group chose Ladders and Snakes, the other chose an amusement park (figure 2). When asked about the choice of game metaphor for the professional development path, they explained it by connecting the world of education to gaming, gamification, and the desire to combine enjoyment in the professional development field. The discussion that formed, became, to our surprise, a disgruntled and full-fledged discourse against external factors such as the Ministry of Education, teachers and school administrators. We gave the discourse time because we felt that the participants needed it, but we realized that the lack of reference to barriers can be problematic in using the tool.

Figure 2. Visual Paths Created by Participants

We gathered all of the participant work products. At the next meeting, we presented the analysis. We showed them the distribution of their responses to the questions and photographs of the paths they created. Then we turned their attention to the meaning of the metaphor in which they choose to represent organizational culture via their path. We fully interpreted the game metaphor they chose, rather than letting them discuss among themselves the meanings that arise from choice. We asked participants to experiment with the tool on different populations to explore options for changing and improving the tool.

4.2 Visual Path of the Workshop Participants

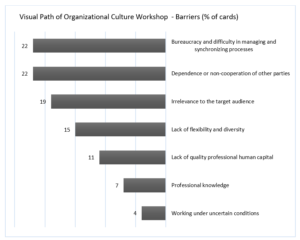

To improve and update the tool, we also used it among workshop participants. In accordance with previous tool usage insights, we requested participants to write on the cards what barriers they encountered as professional development experts. Results of the responses were substantially different (Figure 3). In this case, the population was much more heterogeneous, so that in certain categories, such as new ideas, professional experience, and quality personnel, there were participants who defined these categories as what they wanted to receive, but there were also participants who defined these categories as what they would like to contribute.

Figure 3: Analysis of workshop participant's responses to the tool's questions

The use of ‘barriers’ cards immediately increased the barriers participants encountered, allowing for broader and more open reference to barriers. Although a high percentage of responses dealt with barriers originating from outside entities, such as bureaucracy and non-cooperation from stakeholders, because we provided a platform for presenting barriers, we found that some of the responses dealt with barriers originating from within, such as lack of relevance, diversity, quality of human capital, etc. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Analysis of workshop participant's responses to the barrier question

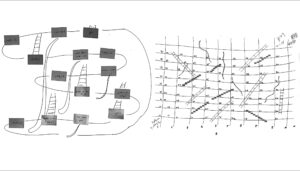

When the participants approached path creation, we found they worked in exactly the same way as their predecessors (figure 5). Of 5 participating groups, 4 chose game simulation paths. In discussion, participants argued the word "path" caused them to turn to this metaphor. We took this claim seriously and began thinking about the possibility of changing our participant guidelines. We asked participants to experiment with the tool on different populations, to explore options for changing and improving the tool.

Figure 5: visual paths created by workshop participants

Only one participant chose to experiment with the tool, choosing to experiment with a group of 7th grade girls. She asked how they view themselves as self-capable. Although the question is not related to professional development, interestingly, none of the girls created a game path (figure 6). One group built a pyramid, explaining:

"Because our goal is to build ourselves, we ask ourselves how does one transcend and build her personality? …. This is the reason we have created a pyramid of floors. The bottom one is the starting point of giving, then you combine the receiving and giving interchangeably.”

The other group built a path representing their class name, explaining:

"We thought about our class, and its character following the decision regarding the placement of the cards. If all the girls would contribute according to their statements, we would have a powerful and strong class. We could actually construct our class accordingly".

We can hypothesize through the girls' story that the word "path" itself does not have the power and ability leading to a uniform metaphor of game, although, in the case of the Psagot teams, the metaphor described their shared organizational culture.

Figure 6: visual paths created by 7th graders

5. Discussion

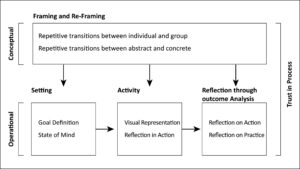

The visual path of organizational culture was developed as a first step in a trans-disciplinary professional development process, as a starting point that will lead employees to develop innovative practices and responses in their area of expertise. From the tool development process and implementation, we extracted a preliminary model, which we believe is a generic model for professional development (Figure 7). Two key parts of the model: conceptual perception and operational stages.

The conceptual framing of professional development offers two key principles:

- Repetitive transitions between individual and group.

- Repetitive transitions between abstract and concrete.

The operational stages include:

Setting – The tool is presented to participants by posing a question relating to a goal. The way we define the question posed to the participants is most significant to the results we receive. Initially, the "state of mind" of the participants must be acknowledged, to set an atmosphere leading to active participant engagement.

Activity –the heart of the tool. Repetitive interchange between individual, group, the abstract and concrete, is activated. This phase has two main principles: Visual Representation and Reflection in Action.

The repetitive transitions between Visual Representation and Reflection in Action allow for creative ideas to emerge, while allowing for the thinking process to be transparent throughout the activity. Reflection in Action becomes a "natural" process of open discussion. To participant’s surprise, they could "see" their profession in a renewed way, and as a result, understand the need and benefit of a new development process, and the power of the group.

Reflection through outcome Analysis – From many past applications, we learned that one of the major drawbacks in the way professional development tools are used is the lack of professional feedback from activity outcomes. One of the key principles at this stage is to present an array of analyses on the whole group outcome. This presentation allows Reflection on Action. The analysis reveals ideas developed as a complete system of thought, allowing for a discussion based on emerging principles. At the last stage of implementation, it is possible and desirable to also reflect on the practice as a whole, and to discuss the general issue of professional development and its future challenges.

Developing and operating tools for professional development according to the proposed model, in our opinion, creates participant trust in the process and develops their ability to realize the possible contribution of using these tools creatively in their various professional environments. This model advances towards a trans-disciplinary and sustainable model that can be utilized in diverse professional environments.

Figure 7: preliminary model

References

Arcavi, A. (2003). The role of visual representations in the learning of mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 52(3), 215-241

Bennett, J. (1996). Reflective conversation with materials: and interview with Donald Schön. In Winograd, T. (Ed), Bringing design to Software (pp. 171-189). Stanford, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Bonnardel, N. (2012). Designing future products: What difficulties do designers encounter and how can their creative process be supported? Work, A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 41, 5296-5303.

Cross, N. and Clayburn Cross, A. (1998). Expertise in engineering design, Research in Engineering Design, 10 ( 3), 141-149.

Dorst, K. (2015). Frame Innovation. Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT Press.

Eastman, C. (2001). New directions in design cognition: studies of representation and recall. In Eastman, C., McCracken, M. & Newstetter, W. (Eds.), Design knowing and learning: cognition in design education (pp.147-198). Oxford, England. ELSEVIER.

Hanington, B. & Matin, B. (Eds.). (2012). Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Beverly, MA. Rockport.

Helyer, R. (2015). Learning through reflection: the critical role of reflection in work-based learning (WBL), Journal of Work-Applied Management , 7 (1), 15-27.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, USA. University of Chicago Press.

Marcelo, C. (2009). Professional development of teachers: past and future, Sisifu, Educational Sciences Journal, 08, 5-20.

Nicolescu ,B. (2005). Transdisciplinarity – Past, Present and Future. CETRANS – Centro de Educação Transdisciplinar

Pohl, C. & Hirsch Hadorn, G. (2007). Principles for Designing Transdisciplinary Research. München, Germany. oekom verlag.

Rittel, H. & Webber, M. M. (1984). Planning problems are wicked problems. In Cross, N. (Ed.), Developments in design methodology (pp. 135-144). New York, NY. John Wiley & Sons.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, USA. Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco, USA. Jossey-Bass.

Shperling, D. (2018). Effectivity of Prpfessional Development. Herzliya, Israel. Mofet Institute (In Hebrew)

Simon, H. A. (1973). The structure of ill structured problems, Artificial Intelligence, 4,. 181-201.

Simon, H. A. (1995). Problem forming, problem finding and problem solving in design. In A. Collen & W. Gasparski (Eds.), Design & systems (pp. 245-257). New Brunswick, New Jersey. Transaction Publishers.

Sternberg, R. J. & Lubart, T. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3-15). New York, USA. Cambridge University Press.

World Economic Forum, Insight Report. (2018). The Future of Jobs Report [file here].